The impact of gender quotas on the results of the 2016 general election may well be fairly limited in terms of the numbers of new women TDs entering the Dáil.

Certainly, voters will have the option of voting for more women candidates than at any other time in the State’s history.

The letter of the law has been adhered to by most parties, and they have done just about enough not to have their precious State funding slashed, but the spirit of the law has not been respected in many cases.

Box-ticking exercise

Reaching the 30 per cent target of female candidates became something of a box-ticking exercise in certain constituencies as the deadline for finalising general election tickets loomed.

A number of low-profile women were added late in the day, allowing little time to conduct a decent campaign that would allow prospective constituents adequate time to familiarise themselves with the newcomers.

By any objective analysis many of these candidates can only be described as “weak” in the sense that they have little chance of securing seats for the party that has selected them.

In some instances, they had to be coaxed into running by party headquarters desperate to reach the quota by almost any means necessary, raising doubts in the electorate’s mind about their commitment to political life in the first instance.

In other cases, it will become clear as the campaign progresses that some women candidates who were effectively “imposed” will not benefit from the essential support of local organisations, without which success is surely impossible.

Sweeper candidates

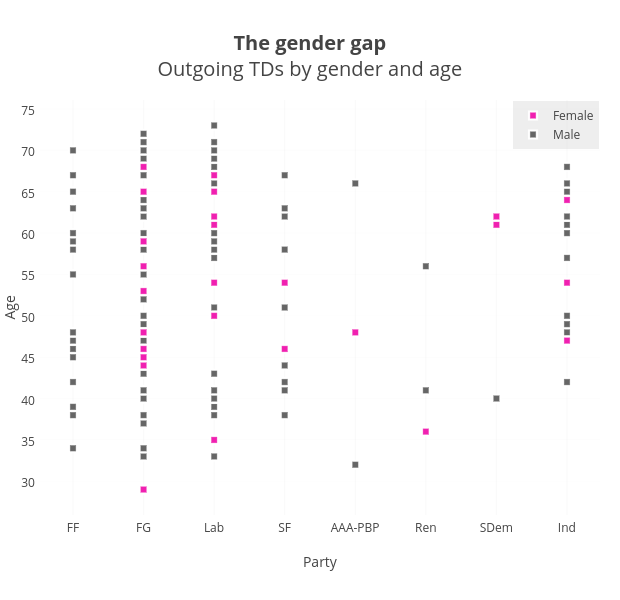

The key problem for the women added on to tickets is that incumbent men remain in place, often reducing the status of the females to that of sweeper or paper candidates.

The culling that some male politicians were worried about did not happen, essentially because parties are in the business of retaining seats.

A total of 25 women were elected in 2011, three more than in 2007 and 2002. It was the highest number of women ever elected in Ireland.

With 166 TDs in the 31st Dáil, just 15 per cent of deputies were women, although the figure crept up to 16 per cent following byelections.

The European average is 27 per cent. It has been estimated Ireland’s slow progress would mean that, without intervention, it could take at least another 40 years, probably much more, to reach equal male/female representation.

Fine Gael TD Áine Collins is optimistic about the quota’s chance of success.

She predicts 40 women will enter the next Dáil, when the number of TDs is being cut by eight.

Nimby approach

However, a “Not In My Back Yard” approach to gender quotas was adopted by some male politicians concerned about their own futures.

Many of them say they agree wholeheartedly with the idea of getting more women into politics, but they do not seem to want it to happen in their own constituencies and at their own expense.

“Everybody’s in favour of it, but maybe in the constituency next door,” was one party strategist’s wry assessment of a tricky situation.

Sympathy may be growing at local level for the men refusing to go down without a fight.

These men have toiled in the political field for many years, often at great expense to their family life.

The nightmare scenario for headquarters is that a female candidate does not receive the backing of a disgruntled local organisation that is essential for a successful campaign.

The issue of quotas is not a significant one for parties such as Labour and Sinn Féin.

Both parties have a good track record in putting forward women candidates and have been well ahead of the 30 per cent mark for some time.

However, for Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil, the introduction of this cultural change has been a painful and sometimes embarrassing process.

One politician, who is in favour of quotas but critical of how they are being implemented, said: “Now they’re trying to throw women into the deep end. Some of the women being added have no hope of getting elected.”